Journal entries (JEs), the foundation of all accounting processes, are used for accurately recording every financial transaction in the account books.

Knowing how they work is key in maintaining accurate and reliable financial records, which you need for both decision-making and regulatory compliance.

This guide is also related to our articles on understanding journal entries in accounting, double-entry accounting: the basics, and how to read a balance sheet.

- Basic journal entry examples

- Adjusting journal entries

- Complex journal entries

- Correcting journal entries

- Journal entries in accounting

Let’s start learning!

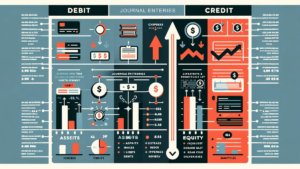

The anatomy of a journal entry

As a small business owner, keeping track of every dollar that comes in and goes out of your business is an important part of your job. That’s where journal entries (JEs) come in handy. They’re the building blocks of your financial records, helping you keep your accounts accurate and up-to-date.

Put simply, a journal entry is a record of a transaction in your accounting system. Each entry logs the movement of money, detailing how funds are coming into or going out of your business. They’re like diary entries for your company’s finances, providing a real-time snapshot of your business’s financial health.

Overview of the structure and components of a journal entry

A journal entry has a straightforward structure but is packed with important details. Let’s break it down:

- Date: When did the transaction happen? Recording the date helps you track when money moved.

- Description: What was the transaction for? This brief note gives you context, like “Office supplies purchase” or “Client payment received”. Make it clear and concise. Anyone reading your journal should understand why the transaction was made.

- Ledger accounts: Where is the money coming from or going to? You’ll have at least two accounts affected by each transaction, showing which parts of your business are involved.

- Debits and credits: The essence of double-entry bookkeeping. If you’re putting money into an account, that’s a debit. Taking it out? That’s a credit. Remember, every transaction will balance out, with total debits equaling total credits. This can get tricky, but just remember that every action in your business finances has an equal and opposite reaction. Sold a product? Debit your Cash account (money in) and credit your Sales account (revenue up). Purchased supplies? Debit your Expense account (cost up) and credit your Cash or Payables account (money out).

Understanding how to put together a journal entry might seem daunting at first, but it’s a skill that becomes second nature with practice.

Basic journal entry examples

Navigating your business’s finances means recording every transaction with care. Let’s look at some basic, oft-encountered journal entries.

Example 1: Cash sales transaction

When you sell something and get paid in cash, two things happen: your cash goes up, and your sales increase. Here’s how to jot that down:

- Debit Cash (increases your asset)

- Credit Sales Revenue (increases your income)

For example:

If you sell products worth $500 cash, you’ll debit your Cash account and credit your Sales Revenue account by $500 each.

Example 2: Purchase of inventory on credit

Buying inventory on credit means you’ll pay for it later. This transaction increases your inventory and adds to your accounts payable (the money you owe).

- Debit Inventory (asset goes up)

- Credit Accounts Payable (liability goes up)

For example:

Bought $1,000 worth of inventory on credit? Debit Inventory and credit Accounts Payable by $1,000.

Example 3: Depreciation expense recording

Over time, big purchases like equipment lose value. Depreciation spreads this cost across the item’s useful life. This way, you reflect the decreasing value of the asset and the expense it generates annually.

- Debit Depreciation Expense (expense goes up)

- Credit Accumulated Depreciation (asset value goes down but in a contra asset account)

For example:

If a piece of equipment depreciates by $200 annually, you’ll debit the Depreciation Expense and credit Accumulated Depreciation by $200.

The key is understanding the flow: what you’re gaining vs. what you’re giving up or what obligation you’re creating.

Adjusting journal entries

Adjusting journal entries are made to update your books between accounting periods. They ensure your records match up with the real-world numbers. Think of them as little tweaks to make sure your financial statements are spot-on at the end of the year.

Adjusting entries are made at the end of an accounting period. They adjust incomes or expenses that haven’t been recorded yet or need to be allocated differently across periods. This step follows the matching principle in accounting, that revenues and associated costs are recognized in the same period.

Example 1: Accrued expenses

Accrued expenses are costs you’ve incurred but haven’t paid for yet, like utilities or wages at the end of the month. You need to record these expenses in the period they occur, not when you pay them.

- Debit Expense Account (increasing your expense)

- Credit Accrued Liabilities (increasing your liability)

For example:

If you owe $300 in wages at month’s end, debit Wages Expense and credit Accrued Wages Payable by $300.

Example 2: Prepaid expenses adjustment

Prepaid expenses are payments made for goods or services to be received in the future. Over time, as you use the service or consume the goods, you need to adjust the prepaid expense account.

- Debit Expense Account (to record the expense)

- Credit Prepaid Expense (to decrease the asset)

For example:

Paid $1,200 for a year’s insurance? Each month, debit Insurance Expense and credit Prepaid Insurance by $100 to adjust for the monthly cost.

Example 3: Revenue recognition before cash receipt

Sometimes, you earn revenue before receiving the cash, like completing a project before invoicing. You must record this revenue when earned, not when received.

- Debit Accounts Receivable (increasing your asset)

- Credit Revenue (increasing your income)

For example:

Finished a project worth $5,000? Debit Accounts Receivable and credit Service Revenue by $5,000 to recognize the income, even if the check hasn’t landed yet.

Reversing journal entries

Reversing journal entries might sound complex, but they’re here to simplify your life. After you’ve made adjusting entries at the end of a period, reversing entries help clear the slate at the start of the new period. They’re particularly handy for avoiding double counting and ensuring smooth accounting cycles.

What are reversing entries?

Reversing entries are made at the beginning of a new accounting period to cancel out certain adjusting entries from the end of the previous period. This is mainly done for accrued incomes and expenses that have now been realized. It’s a clean-up move that makes recording upcoming transactions easier and more accurate.

Example 1: Reversing accrued income entry

Let’s say you recorded income earned but not yet received at the end of the month. When you actually get paid, reversing the initial entry prevents you from counting the income twice.

- Debit Accrued Income (to decrease your asset)

- Credit Income (to decrease your income recorded in advance)

For example:

If you accrued $2,000 of income last month, reverse it by debiting Accrued Income and crediting Income for $2,000. This clears the accrual and prepares your books for the actual cash receipt.

Example 2: Reversing accrued expense entry

Similar to income, you might have accrued an expense at the end of a period for something not yet paid. Reversing this entry when you pay the bill keeps your expenses from being recorded twice.

- Debit Accrued Expenses (to decrease your liability)

- Credit Expense Account (to decrease the expense recorded in advance)

For example:

Accrued $500 in wages last month? Start the new month by debiting Accrued Wages Payable and crediting Wages Expense for $500. This wipes the slate clean for when you issue the actual paycheck.

Complex journal entry examples

From time to time, you’ll encounter transactions that are a bit more involved. Here are examples to help with some of those:

Example 1: Loan amortization

When you take out a loan, not only do you pay back the principal amount but also interest over time. Amortization is the process of spreading out these loan payments.

- Debit Interest Expense (increases your expense)

- Credit Cash or Payable (decreases your liability or cash)

For example:

If you’re paying $300 monthly on a loan, with $50 as interest, debit Interest Expense for $50 and Loan Payable (or Cash) for $250.

Example 2: Depreciation

Depreciation accounts for the wear and tear on long-term assets like equipment or vehicles over their useful life.

- Debit Depreciation Expense (increases expense)

- Credit Accumulated Depreciation (increases the contra asset account, lowering the value of the asset)

For example:

For equipment worth $10,000 with a 10-year life, debit Depreciation Expense and credit Accumulated Depreciation by $1,000 annually.

Example 3: Recording bad debts expense

Sometimes, despite your best efforts, some debts turn out to be uncollectible. To account for these losses:

- Debit Bad Debts Expense (increases expense)

- Credit Accounts Receivable (decreases asset)

For example:

If you deem $200 of receivables as uncollectible, debit Bad Debts Expense and credit Accounts Receivable for $200.

Example 4: Equity investment by owners

When owners invest more money into the business, it increases equity.

- Debit Cash (asset increases)

- Credit Owner’s Equity (equity increases)

For example:

If an owner injects $5,000 into the business, debit Cash and credit Owner’s Equity by $5,000.

Correcting journal entries

Despite our best efforts, mistakes happen. Correcting journal entries (JEs) are your go-to tool for fixing them. Whether it’s a slip in classification or a mix-up in amounts, correcting entries helps you set the record straight.

Correcting JEs are needed when you discover errors in your previously recorded transactions. These could be due to incorrect amounts, wrong accounts, or even transactions that got recorded in the wrong period.

The goal here is for your financial statements to reflect the true state of your business finances.

Example 1: Correction of misclassified expenses

Suppose you accidentally recorded a payment for insurance as an office supplies expense. To correct this:

- Debit Insurance Expense (to increase the correct account)

- Credit Office Supplies Expense (to decrease the wrongly increased account)

For example:

If you misclassified $200 of insurance as office supplies, you’ll correct it by debiting Insurance Expense and crediting Office Supplies Expense by $200.

Example 2: Adjusting entries for inventory errors

Mistakes in inventory recording can significantly affect your cost of goods sold and, consequently, your profit. You want your finances to accurately reflect your stock levels and costs.

- If you’ve understated your inventory, Debit Inventory and Credit Cost of Goods Sold (to decrease it).

- If you’ve overstated your inventory, Debit Cost of Goods Sold and Credit Inventory (to increase it).

For example:

If you find out your inventory was understated by $500, debit Inventory and credit Cost of Goods Sold by $500 to correct it.

Conclusion

We’ve gone from the structure of a journal entry to more complex adjustments and corrections–so now it’s time for you to get involved. Using the examples provided, try creating and analyzing your own journal entries so you can get comfortable with them.

Keep practicing, stay curious, and always strive for clarity and accuracy in your financial records.

Next, check out our articles on how to calculate burn rate, cash vs. accrual accounting, and 10 best peo companies in 2024.

FAQ: Mastering Journal Entries: A Comprehensive Guide with Examples

Here's some answers to commonly asked questions about Mastering Journal Entries: A Comprehensive Guide with Examples.

What is a journal entry in accounting?

A journal entry in accounting is essentially a record of a financial transaction, capturing the movement of money into or out of a business. It’s made up of key components such as the date of the transaction, a description of the transaction, the ledger accounts affected, and the amounts debited and credited.

Why are adjusting journal entries necessary?

Adjusting journal entries is needed for aligning your books with the actual financial situation of your business. They’re typically made at the end of an accounting period to record revenues and expenses in the period they occur, not necessarily when cash changes hands. This includes adjustments for accrued expenses (like wages payable), prepaid expenses (such as insurance), and revenue recognition.

How do you correct errors with journal entries?

Errors in previously recorded transactions can be corrected using correcting journal entries. If a transaction was recorded in the wrong account or for the wrong amount, a correcting entry will debit one account and credit another to balance the mistake. For instance, if an expense was misclassified, you would debit the correct expense account and credit the originally debited account to reverse the error.